ABOUT

Rotunda

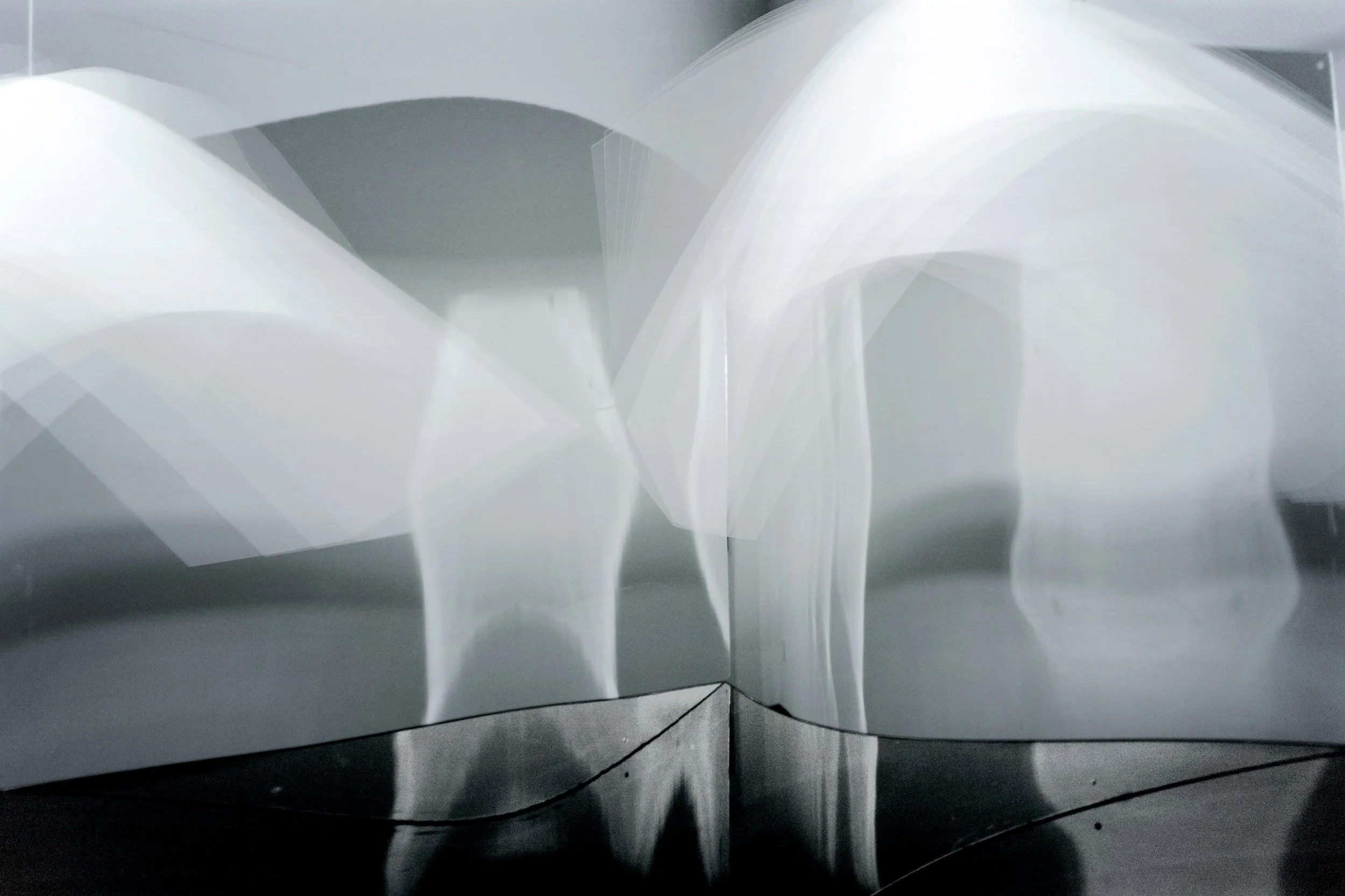

Adam Swica’s studio-constructed photographs regularly enlist projected light as a shaping device, whether resolving in pictorial scenes or recording dimensional volumes through multiple or time exposures. While often involving the building of large sets, his latest suite of works under the title, Rotunda, charts a reductive approach, where light itself is shaped through reflection, projection and reflected projection. While without material contours, save for a small corner of the image, light masquerades as form. Shooting on film and utilizing multiple exposures, Swica coaxes an interior volume of domed canopies and multiple, recessed spaces. Likened to sound, light is pictured as a permeating quality: structural yet ethereal, responsive.

Currently on view @ CHRISTIE CONTEMPORARY, Toronto

Daybreak

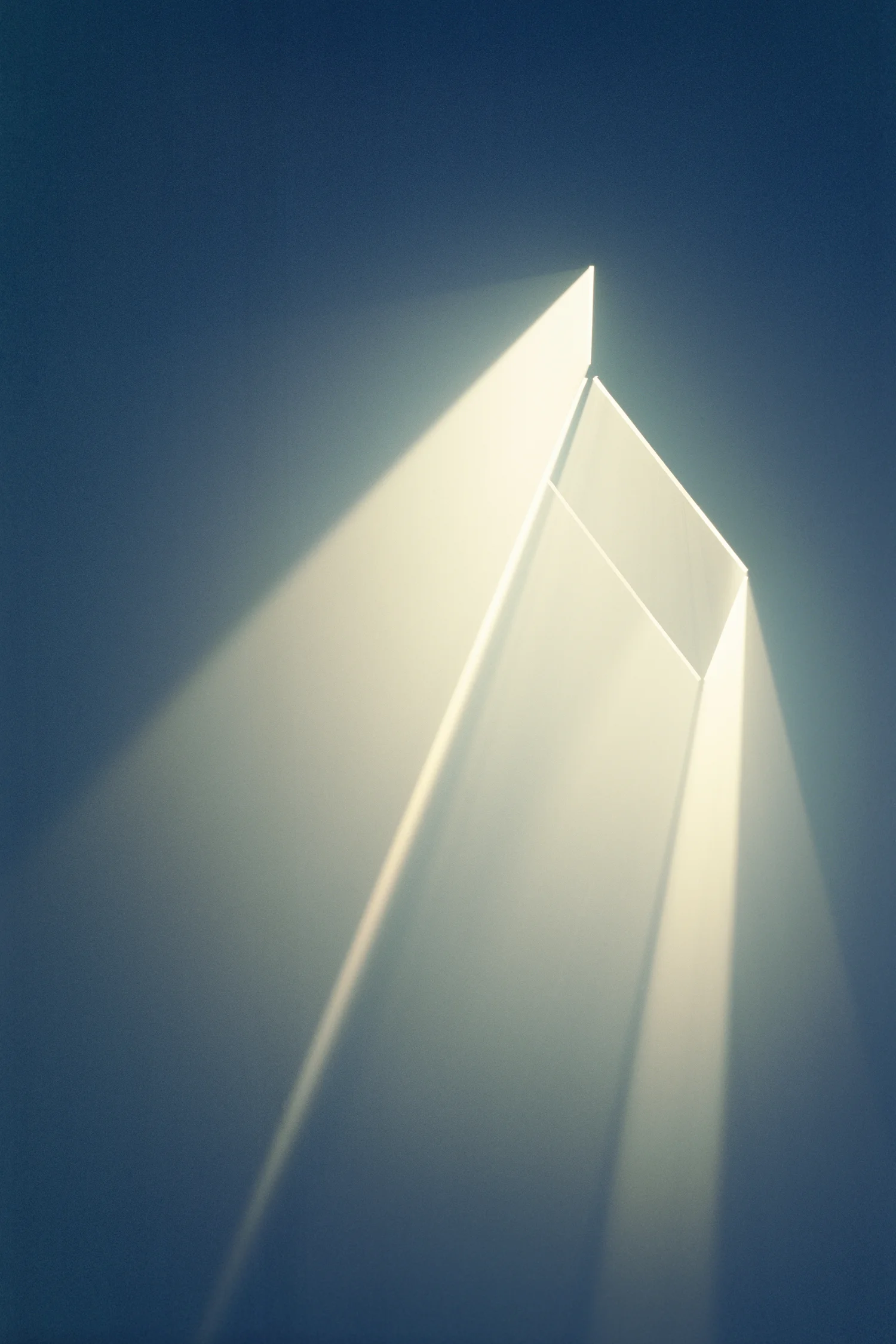

A single image is pressed into memory, recurring, but different every time. In this new series of composite photographs created in his studio, Adam Swica recreates a set of conditions that, for a brief moment at dawn, cast day into night. The repeated composition in Daybreak, with its sometimes slight, sometimes dramatic variations, reimagines the myriad incarnations of a momentary light-environment.

At first glance, the richly saturated photographs in Daybreak appear to show the all-too-common view out of a window—a tree, the sky, a landscape in the distance, and some reflections in the glass. These deceptive, intricately constructed images, however, attempt to translate the artist’s impression of a fleeting moment experienced daily at dawn in his studio, when east meets west. Under a range of conditions, morning and darkness coincide in one room—the light cast from an easterly suite of windows reflects through to a westerly, yet unlit horizon. Each photograph in the series operates as a narrow, vertical window, underlining the sense of “viewing through.” Using his benchmark materials—projected light, Cinefoil, cardboard, glass, LED lights, and paper—as well as considerable mathematical calculation, Swica builds both the landscape features that populate the scene and the light-information layered upon them.

This project marks the first time that Swica has worked iteratively—typically, his analogue practice involves constructing a large-scale “set” assembled from humble materials, with the intention of capturing a single image, often generated through multiple exposures. The images in Daybreak are driven by the rchangeable and ephemeral nature of the scene repeatedly observed—atmospheric changes, density of reflection, and colour variations transform each rendering of an elusive moment into a possible, or an impossible, view. Swica’s methodology invites the viewer to share in the hazy layering of light that characterizes this brief flickering in time, when day and night are glimpsed together.

Expanding the work into three dimensions, and as a new aspect of Swica’s approach to presentation, the exhibition also features an installation of the Cinefoil foliage and an artifact of the light aperture that populated the set

Somewhere

Echo. Location.

Memory is a reconstructive process, a mind’s eye image generator drawing from a complex catalogue of experiential data, rendering the possibility of the ‘familiar.’ Photography is in some measure its mechanical corollary, fixing a moment, by reference, in perpetuity. When we look at a photograph, we search for the familiar—person, place or thing—functionally triggering memory at the level of recognition. Adam Swica’s series, Somewhere, suggests a reversal, working on the notion that a memory could trigger a photograph.

Absent the original place, Swica builds dimensional views using humble materials—plastic, foil, styrofoam, cardboard, mirrors, water, salt—creating sprawling sets ranging up to twenty feet wide and several feet deep and high in scope. Simulation is not in evidence here, with forms often crudely suggestive of something, rather than sculpturally accurate. With the introduction of light, the essence of proportional delineation to the eye, the constructions transform into spatial atmospheres, often guided by a line in horizon, fixing the idea of ‘place.’ From here, the photographic image consolidates the trajectory of recall, construction, resonance.

As photographs, these subject hybrids hover at the median between real and perceived to be real, between being read as recorded locations and memory objects, as each image subtly declares its own charade as a material contrivance—the damp rippling of craft paper, the rigidity of thick plastic, the slick stretching of plastic wrap. Yet these signposts to visual deception, hardly uncommon to the current dominion of photography, do little to interrupt or short-circuit the photographic impression, determining instead their tautological potential as place. They quietly persist as image conundrums that resist the imperative to solution.

Contemplatively spare, the images largely relate unspoiled views captured at a distance, and accumulate the features of time as a moment suspended. They are at once familiar and unknowable, even the detection of their fakery only seeming to underscore their insistence as a somewhere. The analogue photograph is inarguably a rhetorical object, but here, with each image assembly built and destroyed, the photograph additionally assumes the legacy of that which formed the genesis of its making: memory.

— Claire Christie

Deconstructed Landscapes

From postcard to panorama the landscape image occupies a particularly powerful hold on our perceptions of place and memory. Viewing landscapes can trigger a variety of responses in the viewer. These might include nostalgia, awe, vertigo, a sense of calm or even longing. One of the measures of the ‘success’ of the landscape form is dependent on how well the image convinces the viewer of the presence of depth and distance. If this quality is in play they can project themselves into the perceived space, achieving a sense of ‘being there.’ At its best one feels a palpable sense of atmosphere and a perception of infinite distance. At worst we have a billion bad sunset vacation photos to offer as evidence, and a reason that the form is considered by some to be a cliché.

Adam Swica’s landscape photographs explore the edges of physical perception and suspension of disbelief. His experience as a director of photography in the film industry where expert misrepresentation is the norm gives him a unique perspective and skill set to accomplish this. Nothing is real in the world of film—everything is created from an idea in the script to elicit a response or an emotion in the viewer. What we see on the screen is entirely a construct. The structure and workflow of a film production is planned and executed carefully and while the result can be evocative, moving or disturbing—all the values we might associate with viewing a movie—the production process can seem a bit bloodless by comparison. It is from this ironic place that these photographs have their beginnings.

The dichotomy between actual and perceived reality is at the core of Adam Swica’s photographs. Using mostly mundane materials— styrofoam, cardboard, tissue paper, wire and plastic sheeting—he builds ‘sets’ which depend on the properties of each material to represent something else. Though modest and raw in their simplicity they are highly calibrated to give a convincing ‘performance’ in their assigned ‘roles.’ The materials are not really disguised—staples, tape, and other evidence of the construction process—‘tells’ may be openly visible. They retain their literal character but because of change in scale and context they begin to become something else. They are lit and shot with the production values of a feature film and the line between the raw elements in the set and the depicted scene is mostly dissolved as the new ‘reality’ emerges. Once the negative is scanned, the set is dismantled and he moves on to the next image much as a film crew moves to the next scene in production. The ‘script’ that informs these images evolved from the idea that ‘real’ landscape photographs were too open to interpretation and could be ‘read’ in many ways. Whether taken from actual or imagined places, Swica wanted to narrow the focus of each scene and by working in the studio, where utilizing the controls of set, lighting and camera they achieve a dreamlike quality, a kind of fugue state between conscious and unconscious perception. It is through this prism that the viewer experiences the responses associated with ‘reading’ landscapes and enters Adam Swica’s visual world.

— Paul Orenstein

Placeholders

Adam Swica’s analogical, studio-constructed photographs investigate the volumetric geometry of light. The Placeholders series transforms historical constellation patterns into dimensional image fields, where simple line drawings are projected into a particulate atmosphere, essentially a container for light, and captured by the recursive lens. Interested in how the naming of constellations essentially converts abstract arrays into recognizable forms, Swica returns these simple pictograms back to the threshold of abstraction, creating ethereal vector projections. Working with a range of constellation subjects, Swica plots the lines between his celestial coordinates and then reverses them out of the projected surface to form the outline of the light object itself. Using long exposure times and multiple exposures, Swica captures evidence of light in transit—the permeation of light through space and time—revealing an abstracted image of his constellation’s proportions in a volume of otherworldliness. This “materializing” of light alludes to early astronomy, where points of light were perceived through time and over distance, connecting the planet to the larger universe, with the constellations attempting to fix a sense of place. Swica’s luminous projections suspend what must have been that original sense of wonder.

Ellipsis

Adam Swica’s photographs under the series title Ellipsis probe the durability of the photographic gesture, or capture, in the making of a photographic object. Through the mechanisms of multiple and time exposures, Swica uses light, movement, and duration to coax dimensional planes within the photographic frame.Shooting on film, Swica physically shifts sheets of coloured construction paper and inscribes the repeated movements onto a single negative. Variations in opacity and translucency are determined by the durational light of a long exposure. Each photograph contains anywhere from 20 to more than a 100 gestures, with successive captures potentially infringing or obliterating preceding ones. Swica’s methodology involves memory at the level of cataloguing the sequence of shots, and chance at the level of comingled photographic events. The in-camera building of the image is an active yet unpredictable construction, situated somewhere between an automatic drawing and an architectonic structure.

With the unfolding of motion compressed into one frame, repeatedly recorded elements emerge as complex geometries. Their trajectory is reconfigured as an ethereal, contiguous whole, a volume sculpted by light through time.

Tumble

The genres of both constructed and abstract photography acknowledged a paradigm shift with the advent of digital technologies, loosing the “what-has-been” characteristic of photographic capture to include the “what-is-imaginable” availed by imaging techniques within the computer environment. Sandwiched between these two ideals, constructed and abstract photographs acquired a unique position within the discipline. Early examples featured the appearance of the real and the real made abstract by magnification or some measure of distortion, challenging our perceptions of “what-has-been” at the level of visual evidence, whereas the current proliferation of digitally generated images ironically confers a condition of authenticity to these once elusive image models.

Proceeding from a series of constructed landscapes, where Adam Swica harnessed the transformative potential of humble materials to serve pictorial function, the abstractions under the series title, Tumble, pursue non-objective fields of form and colour achieved through the same means, with the initial building of a sculptural model as subject, made animate by light. Here, the construction of a wall of paper fragments spanning seventeen feet across and eleven feet high created an enmeshed agglomeration of irregular paper strips, some blank while others bore traces of surrendered test prints. Swica isolated large details within this expanse — itself a series of cropped details — introducing two points of magnification within the same frame. Chance voids and arcs, and glimpses of printed imagery excised from their contextual whole, coalesce into an active, gestural matrix upon which Swica projects filtered light, amplifying both connections and disturbances within the field. Flat planes become unified by colour and read as marks darting across a surface, often with a second or third colour articulating additional strata, while dark hollows insist a churning depth. The dimensionality of the constructed field — its objectness — in combination with the flattened layers of colour — almost a paean to the digital — make the images’ origins difficult to reconcile. They flicker between active and still, porous and opaque, structural and dissolute, but despite their abstracted form, the images ultimately maintain allegiance to the tangible, to the “what-has-been.”